Let’s All Try the Optimal Energy Diet

Jul 18, 2023

Instead of cutting calories, see what happens when you eat enough.

By Selene Yeager

Like many of you, I grew up with the mentality that you should always be “watching what you eat” and aiming to “eat less.” Even while racing on a professional level, I’d sit at dinner with athletes (including myself sometimes) who wouldn’t touch bread. The focus was never on how much we should be eating. It was how little we could eat.

Never mind that it often backfired. My weight would yo-yo under the stress of deprivation, training, hormones, inflammation, and life. My performances weren’t consistently better at lower weights or worse at higher weights. Looking back, and examining the present, the only nutritional strategy that ever consistently improved how I felt and performed was eating enough—being properly fueled for the work and recovery at hand.

That message is especially important for females because our stress response is more sensitive to low energy availability (LEA). As Dr. Julie Foucher of Wild Health explained on a recent episode of Hit Play Not Pause when you don’t support your training with enough calories and/or carbohydrates, your performance and health eventually suffer and, if your goal is fat loss, it can be more difficult because your body will hold onto fat stores.

It also hinders muscle growth. A recent study on 30 trained, naturally menstruating females found that 10 days of endurance and resistance training with LEA impaired myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic muscle protein synthesis (i.e. messes up the muscle development process). Compared to when the women trained with optimal energy availability (OEA), training with LEA led to reductions in lean mass, urinary nitrogen balance, free androgen index, thyroid hormone concentrations, and resting metabolic rate.

And that’s among women whose hormonal status is still favorable for muscle making. For women in and beyond the menopause transition, this situation is even more urgent. Especially in midlife, we can’t afford to throw the brakes on our muscle protein synthesis.

Optimize Your Energy Availability

So, what is the Optimal Energy Diet? To be abundantly clear, it’s me being a bit facetious because I come from a publishing background where you’re encouraged to sell everything as a diet. But truly, as far as “diets” go, optimal energy sounds like a great one to me!

Achieving OEA means eating enough. That is clearly often easier said than done since human beings don’t come with fuel gauges (if only…). The best way to dial in your optimal energy intake is to work with a trained sports dietitian who can help you understand how much energy your active body needs and how to meet those needs. But this much is clear: it’s probably more than you think. Research shows that up to 47 percent of female athletes have LEA, which as we’ve written about before can have negative health and performance consequences. Endurance sports athletes are especially at risk because of high training loads and the traditional emphasis on being as lean as possible.

LEA can be particularly insidious among perimenopausal women because the signs, which include menstrual cycle disruption, brain fog, muscle loss, decreased bone density, increased risk of injuries, and/or not responding to training as you used to can be confused with some of the issues that can arise during the menopause transition.

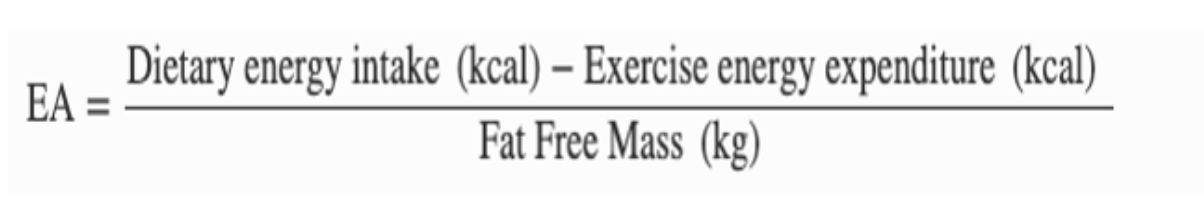

For insights into what OEA looks like, let’s dig into some of the research. The equation for determining energy availability (EA) is defined in the equation below, which after you factor in the calories you’ve eaten and the calories you’ve burned during exercise and divide that by your lean body weight (the weight of everything except fat tissue, or fat-free mass FFM), gives you the energy left for basic metabolic functions.

LEA happens when you end up with an insufficient amount of energy left after your workouts and training to support your normal physiological functions such as metabolic function, bone health, immune function, and the menstrual cycle in premenopausal women.

Though there are no firmly established guidelines prescribing optimal energy availability for high-performance athletes, research shows that for the average sedentary normal weight woman, the target is at least 45 calories per kilogram of fat free mass a day. For someone who weighs 68 kg (150 lbs) and is about 25% body fat (i.e., 51 kg FFM) that would be about 2,295 calories a day. For active women, however, 2,295 would result in low energy availability, because she’ll be burning a few hundred calories during exercise.

For example, say that same woman goes on a two-hour bike ride and burns 900 calories, her energy availability would be down to 27 calories per kg of FFM. Clinical studies show that when you reach an EA less than 30 calories per kg of FFM, your health starts deteriorating after just 5 days. That’s why for women, LEA is defined as <30 calories per kg of FFM. (Note, despite the fact that women are always encouraged to eat less, our threshold for LEA is higher than men’s. Male athletes run into trouble when they have a prolonged EA of < 25 kcal/kg FFM.)

The study cited earlier comparing females training with either OEA or LEA set the bar for OEA at 50. Putting it all together, if you’re 68 kg (150 lbs) and 25% body fat (i.e. 51 kg FFM) and are burning about 500 calories a day exercising, eating 2,900 calories a day will give you an energy availability of 47, right in the sweet spot.

This isn’t a call to whip out your calculators and start counting every calorie. It’s more of a deep dive into the science of how much energy we need and why we talk so much about being properly fueled at Feisty Media.

How to Achieve OEA

Again, the best way to get your nutrition straight is by working with a trained professional. There are also some smart fueling strategies you can incorporate right now to put you on the right path.

Keep up with your carbs

Research shows that getting enough carbohydrates can help you avoid LEA even if/when your total energy is on the lower side. That’s important because so many women still avoid carbs because they fear they will cause unwanted weight gain. Cutting carbs can not only limit your performance, but also harm your health. When it comes to bone health and immunity some studies suggest that carbohydrate restriction is more detrimental to both than not getting enough calories overall.

How much is enough? Most athletes need between 5 to 8 grams per kilogram of body weight, explained Heidi Skolnik, CDN, of Nutrition Conditioning, LLC, and co-author of The Whole Body Reset in episode 103 of Hit Play Not Pause. “You may even need upwards of 10 grams per kilogram depending on your sport,” she says.

Give your muscles the amino acids they need

Active women need to stay on top of their protein needs to make and maintain muscle. Skolnik emphasizes aiming for at least 25 grams in your morning meal. “You need to hit 25 grams of protein in the morning to press that anabolic, muscle-building button,” she explained on the podcast.

Then spread it out throughout the day. “The goal is to have 25 to 30 grams of protein three or four times a day coupled with strength training to help you maintain your muscle, which is crucial for health and well-being across the board,” she says.

Eat earlier in the day

One of the ways women get in trouble with practices like intermittent fasting is they skip breakfast. As Dr. Julie Foucher explained on Hit Play Not Pause, that can leave you under-fueled for your training and sets the stage for low energy availability.

Your hunger hormone ghrelin also increases when you undereat during the day, so you get hungrier as the day goes on. That’s a problem for proper fueling because people end up overcompensating when they do eat, setting them up for a vicious cycle, says Skolnik who recommends trying to eat two-thirds of your calories in the first two-thirds of your day.

“If you want to intermittent fast, that’s what sleep is for,” says Skolnik. “Stop eating at 8:00 p.m. and then eat breakfast the next morning at 8 a.m. That’s 12 hours. You’ve just done an intermittent fast.”

A Word About Weight

During a recent Level Up Membership meeting, a number of women shared their struggles with LEA, which had left them with more musculoskeletal injuries, poorer performance, impaired gut health, and other issues. Though they had been aware of LEA, they didn’t believe it was possible that they had low energy availability because they weren’t skinny. They had what they considered “excess” body fat.

Contrary to the mainstream diet industry messages, fat loss and gain is not a simple equation. People can and do undereat and not lose weight because their bodies adjust to hang onto fat for survival reasons. As Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford explained in episode 113 of Hit Play Not Pause, your body can fiercely defend weight, which is why weight loss is notoriously difficult to maintain. Extreme restriction can trigger the body to favor energy storage, and your brain will dial down your metabolic rate (the energy you use just to function) in response to weight loss, which is why people end up weight cycling (aka yo-yo dieting). Your body is changing your metabolic rate to maintain energy balance—that’s what it wants.

As an example, Stanford pointed to the Biggest Loser contestants, who were put on extreme diet and exercise regimens. Their resting metabolic rates dropped dramatically, making weight maintenance nearly impossible. As reported in Harvard Health, one man lost 239 pounds, finished at 191 pounds, regained 100 pounds, and 6 years later still had a metabolic rate of just 800 calories.

Giving your body the energy it needs to perform your workouts and perform its fundamental metabolic functions is essential for health and performance and maintaining a healthy metabolism.

Get Feisty 40+ in Your Inbox

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason or send you emails that suck!